- Above the noise

- Posts

- The Tractor, The Manager, and The Meme

The Tractor, The Manager, and The Meme

My work sits at the crossroads of AI development and communications leadership, giving me a unique vantage point on the strategies taking shape in both fields. This newsletter is where I distill the emerging themes and connect the dots from these discussions. Given our previous interactions on this topic, I hope you find this latest analysis valuable. This time:

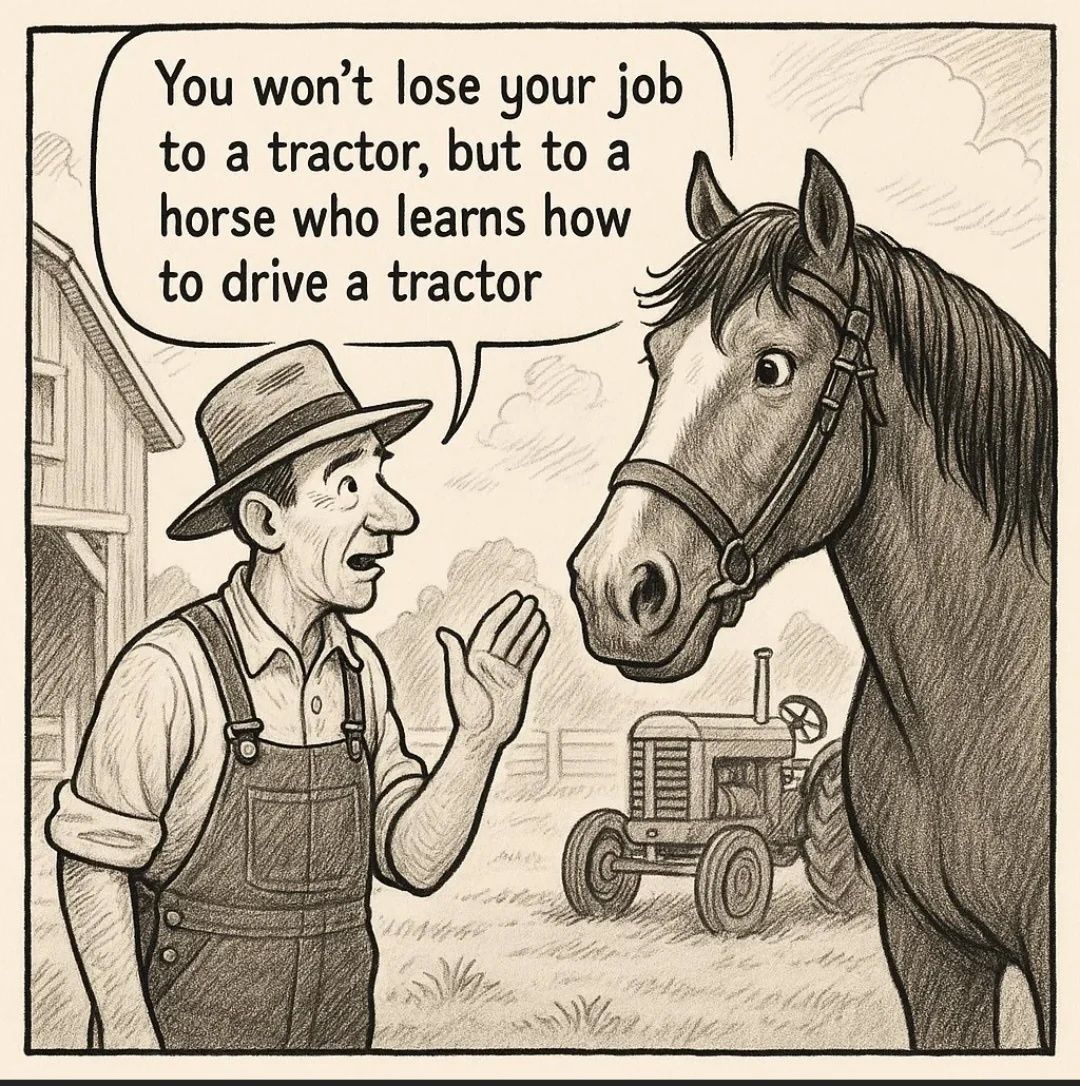

You may have seen this meme making the rounds on social media recently, which is a glib take on a familiar refrain: you won't be replaced by AI, but by a human who uses AI.

“You lose your job to a tractor, but to a horse that learns how to drive a tractor“

The real irony is how this meme gets history completely backward.

Obviously the tractor did not create a new species of tractor-driving horses. It released the horse from the drudgery of field work into a life of relative leisure. The entity whose role was fundamentally and irrevocably disrupted was the farmer (or, the manager). Mechanization drove the percentage of the population employed in agriculture from nearly 90% down to under 10% today.

This parable of the tractor is the best lens through which to view the coming disruption of AI, and it's the managers—not their reports—who ought to be paying the closest attention.

The Modern Manager's Dilemma

The lesson from the farm is that technological revolutions don't just augment existing tasks; they restructure the entire system of value creation. Today’s managers are a high-cost resource, and in many large organizations, their primary function has shifted away from direct value creation. Their role today is primarily managing people and processes that AI is set to automate, coordinate, and optimize. They are the farmers of pre-mechanized agriculture. The 10% of management that survives this transition may not be those who teach their teams to use AI, but those who can architect and manage entirely new, AI-native workflows.

The Adoption Spectrum: Type A, B, and C

Of course, we still don’t know how this change will ultimately play out, but we’ve now had enough direct observation and experience of AI implementation and its economic impact to start forming some theories. Our experience has shown three distinct organizational approaches to AI adoption.

Type A: Bottom-up Adoption

This is the default enterprise AI strategy, and it should be a familiar one. It mirrors the early days of the PC revolution: put a new tool on every employee's desk and assume productivity will naturally follow. The strategy is predicated on the idea that access is the same as integration.

The stated goal is to empower employees and boost productivity. For leadership, this is an easy decision to make; it’s a manageable, predictable action item that feels like progress.

The disconnect, however, appears in how success is measured. This approach is not a strategic exercise measured by its impact on core KPIs like cost reduction or cycle time improvement. Instead, success becomes a numbers game of proxy metrics: adoption rates and "feel-good" survey results. The measurement is about usage, not outcome.

This reveals the implicit mandate: the fundamental aim is to make the current way of working slightly faster, leaving the underlying processes—and all their inherent inefficiencies—fully intact.

Figuratively the goal is to help an employee write an email faster, not to build a system where that email is no longer necessary. The organization treats AI as a perk, not a paradigm shift, pushing the onus for finding value down to the individual employee. It is a strategy built on hope—the hope that thousands of isolated acts of minor optimization will somehow, in aggregate, equate to transformation.

Type B: Top-Down Revolution

This is the rarer—and far more potent—approach. It views AI not as a tool for the worker, but as a new foundation for the work itself. This is not the PC-on-every-desk model; this is the assembly line.

The starting point is a first-principles look at the business: systematically mapping processes and their associated costs. The goal is not to augment the existing workflow but to ruthlessly identify opportunities to rewire the entire process around AI.

Here, success is not a survey; it is a P&L statement. The metrics are unambiguous: time, cost, and output. Management makes a clear-eyed decision on the benefits, accepting a new process so long as the quality remains within an acceptable threshold—a threshold often defined by “good enough” rather than perfection.

This exposes the fundamental conflict between the two models, which is ultimately a psychological one. In a Type A organization, humans are incentivized, consciously or not, to protect their own value. An AI-assisted process will always be judged as "90% as good" as the old way, because to admit otherwise is to devalue one's own role. Employees will always find one or two reasons why the new system “just isn’t quite ready yet.” This creates a Human Bottleneck, where meaningful change is impossible until an AI is undeniably 200% better than the existing process.

A Type B organization, by contrast, bypasses this bottleneck entirely. It will happily—and rationally—accept 90% of the previous quality if it comes with a 50% reduction in cost or time. That is not an emotional calculation; it is a business one. And it is why this approach, while harder, is the only one that leads to genuine transformation.

The Value Capture Gap

This difference in approach leads directly to a difference in outcomes, and it explains an issue widely reported by many analysts: that while AI adoption is widespread, its economic impact remains elusive. The key challenge is that companies are achieving widespread Personal Value Capture while failing to unlock meaningful Organizational Value Capture.

Our observations suggest this isn't a puzzle at all; it is the predictable result of the dominant adoption strategy.

Personal Value Capture (The "Type A" Outcome): An employee uses an AI tool to create a press release 15% faster or write LinkedIn posts more eloquently. This is a real benefit to the individual—it makes their job easier—but it doesn't save the company money (the employee still draws the same salary) and it doesn't increase revenue. It's a productivity gain that dissipates into the organizational slack. This is the hallmark of the Type A, bottom-up approach, and it is where the vast majority of companies are today.

Organizational Value Capture (The "Type B" Outcome): A company uses AI to re-architect its campaign planning process. A workflow that took three people five weeks to resolve now takes one person, augmented by an AI solution, one day to manage*. This is a tangible difference to the bottom line. It's a structural change that yields durable cost savings and speed advantages. This is the exclusive domain of the Type B approach.

The reason organizational value capture is so evasive is that most companies are, by default, Type A. They are distributing tools, not redesigning systems. The economic pressure isn't yet acute enough to force a more radical, and frankly more difficult, approach. This is due to a combination of organizational inertia and the fact that we are still in the early innings of this technological wave. But the pressure is steadily building, and the gap between the value capturers and the rest will become very real.

The Pragmatic Path: The Type C Strategic Hybrid

While Type B represents the theoretical ideal for disruption, its "ruthless" nature can be a non-starter in established organizations. This is why a third, more pragmatic path is emerging. This is the path of smart, persistent evolution.

The Strategic Hybrid rejects both the passive hope of Type A and the high-risk, all-or-nothing gamble of Type B. This approach understands that transformation is not a single event, but a process built on momentum.

Instead of attempting to boil the ocean, these firms identify a single, high-leverage problem: a workflow defined by extreme cost or inefficiency. A small, dedicated team is then deployed with a clear, metric-driven goal, reporting tangible improvements against existing KPIs.

The most important outcome, however, is not the immediate ROI. It is the accumulation of internal credibility and political capital. This is not a radical re-engineering that terrifies the organization and triggers the Human Bottleneck. It is a persistent, evidence-based campaign that proves the value of AI, one workflow at a time.

Each successful project provides the air cover and organizational buy-in for the next, more ambitious one. The ultimate goal of a Type C strategy is to earn the right to execute a Type B transformation.

The Inevitable Reckoning

The current landscape is clear: most companies are dabbling with AI in a Type A fashion. They are buying the tools, encouraging experimentation, and hoping for the best.

This is not likely to be a winning strategy: The market is already beginning to bifurcate. On one side will be the Type B revolutionaries who will seize an enduring competitive advantage built on a foundation of superior cost and speed, which will later translate into superior quality. They will set the new benchmark. On the other side will be the incumbents. The only ones who will thrive are the Type C hybrids, who understand that true adaptation requires a methodical, trust-building approach to rewiring their operations from the inside out.

So, what is the path for the leader who recognizes this threat? The good news is that a clear, pragmatic path is emerging. Based on what we have seen work effectively in organizations successfully making this transition, the journey to becoming a Type C organization begins by changing the questions you ask.

First, the leaders we see succeeding shift their focus from the tool to the problem. They stop asking, "What can our team do with AI?" and instead ask, "What is our most broken, high-cost, or soul-crushing process?" Their first job isn't to become AI experts; it's to become ruthless experts on their own team's inefficiencies and to identify a single, high-impact target.

Second, the effective approach we've observed is to start small and prove value surgically. Instead of a broad, low-impact rollout, they form a small, dedicated team to attack that one, well-defined problem. The goal is never framed as "experimenting with AI," but rather as "solving this specific business problem using AI." This creates focus and a clear definition of success.

Finally, the most crucial difference we've seen lies in measurement. These successful teams ignore superficial metrics such as adoption rates. They obsessively measure what matters: cycle time, cost-per-activity, error rates, audience engagement or other core business KPIs. A tangible win—like a 40% reduction in the time it takes to complete that broken process—is the only currency that builds the credibility and organizational trust needed to scale. This first step might feel slow, but it builds the foundation of skills and political capital for the next, bigger move.

Which brings us back to the meme.

The leaders sharing it believe they are leading their teams into the future. In reality, they are revealing a Type A mindset—handing a new tool to the horse while leaving the fundamental structure of the farm unchanged. They are missing the strategic implications of the tractor itself, focused on the worker, not the work. And that is a mistake that, just like for the farmers before them, could prove to be existential.

*We have actual examples of this in practice.

This is my current analysis of a rapidly evolving landscape. I welcome pushback, different perspectives, or data that challenges these theses. The smartest thinking on this topic will come from a collective effort.

As this technology gathers pace, we are all navigating a fascinating new chapter, and the full story is still being written. I look forward to exploring it with you.

And.. if you are still reading this and still want more you can read my archive of previous posts.